Contents ▾

Creating event sourced aggregates with C#

In this post I’ll cover a minimal example showcasing an event sourced aggregate. The main points of interest herein are the development of a generic event sourcing approach for aggregates, a solidification of the access patterns and the development of unit tests.

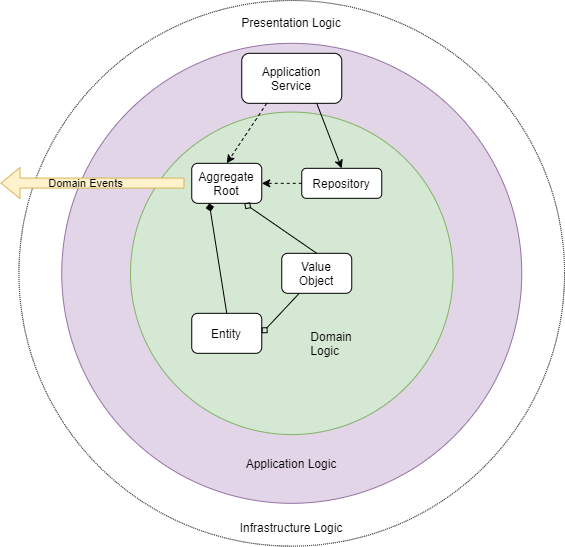

As part of this post I assume the domain is isolated within its own assembly within the project, providing us with additional techniques to isolate internal aspects from the external world (domain consumers). The main concept herein is that isolation of the domain allows us to have more fine-grained control over the code running within this boundary.

Though I would consider event sourcing in itself mostly an infrastructure concern, especially due to the way events are stored, retrieved and applied, the aggregate that must be event sourced must have an interaction pattern which lends itself to such approach. This interaction pattern is the exact thing I will be focusing on throughout this post.

Plumbing

In order to create a generic base from which to develop aggregates which support this interaction pattern I’ll start by introducing three pieces of plumbing. By generalizing this code we’ll be able to focus on domain logic later on without needing to consider implementation details. What is needed:

- An interface defining the command’s required behaviour

- An interface defining the event’s required behaviour

- An abstract aggregate defining how

- Commands can be validated

- Events can be applied

Both interfaces are as minimalistic as possible, and only focus on the sole thing they should be able to do. For the command that is the validation of provided information, while the core feature of the event is to apply the provided data to the state.

public interface ICommand<TState>

where TState : Aggregate<TState>

{

public IEvent<TState> Validate(TState state);

}

public interface IEvent<TState>

where TState : Aggregate<TState>

{

public void Apply(TState state);

}

The abstract aggregate in turn is solely responsible for tying the commands and events to the DTO representing the aggregate data. The job it does is to ensure that commands and events alike can only be used against a concrete aggregate implementation. As part of that job it uses generics in a rather opque way to ensure the actual implementation is closely coupled with the aggregate behaviour as defined in this class. By constraining the generic type to be one of its own we can confidently cast any instance to type T, which is beneficial for handling the validation and mutation logic.

public abstract class Aggregate<T>

where T : Aggregate<T>

{

// Ensure we're only able to use this class in the domain itself

internal Aggregate() { }

public IEvent<T> Validate(ICommand<T> @command) => @command.Validate((T)this);

public void Apply(IEvent<T> @event) => @event.Apply((T)this);

}

It’s with these relatively simple lines of code that we’re able to rigidly structure the interaction pattern to and from aggregates.

Aggregate implementation

Now that the dependencies are in place we can focus on the design of the aggregate itself. For the sake of simplicity I’ll crudely model the User aggregate;

public class User : Aggregate<User>

{

public string Name { get; internal set; }

}

Through this simple class we already made sure that its properties cannot be modified from outside the domain assembly. The only way to do so would be through issuing commands.

To give some sense to the collection of objects required for this approach I model a parent class to represent the operation we’re executing on the aggregate (in the example being UserCreation). As part of this class I add three more subclasses;

- One holding the actual command/event data

- A concrete command implementation

- A concrete event implementation

An example of these things together is shown beneath;

public class UserCreation

{

public class Data

{

internal Data() { }

public string? Name { get; init; }

}

public class CreateUser : Data, ICommand<User>

{

IEvent<User> ICommand<User>.Validate(User state)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(Name)) throw new Exception("Name must not be empty");

return new UserCreated(this);

}

}

public class UserCreated : Data, IEvent<User>

{

internal UserCreated(Data data)

{

Name = data.Name;

}

void IEvent<User>.Apply(User state)

{

state.Name = Name;

}

}

}

A few notes about the considerations in the snippet above:

- A new instance of the

Dataclass can only be instantiated internally; this to prevent external dependencies inhibiting any future refactoring efforts - The

CreateUserclass is the sole component knowing when to issue an instance of theUserCreatedevent. - The

UserCreatedevent can only be initialized internally; to prevent unauthorized events from being applied. - By explicitly implementing the

ICommand<T>andIEvent<T>interfaces we ensure those remain hidden to outside consumers of the actual implementations.

This way we hold a relative amount of freedom regarding internal affairs of the domain, while pinning down the interaction pattern required for external consumers of the domain. Now we can be fairly sure the following flow happens whenever a mutation is dispatched:

- A command is created

- The aggregate can exchange the command for an event

- The resulting event can be applied towards the aggregate to update its internal state

This rigid structure gives us the certainty that whenever a domain consumer has gotten a hold of an event that;

- All required data is available on the event object

- The operation has been validated against the current state

At the same time this provides us with a lot of freedom for any implementing parties since they can at least do the following;

- Hold it in memory until a number of commands have been properly validated

- Store it on the event journal to reconstruct the aggregate sometime in the future

- Dispatch the event on messaging infrastructure to notify other components of the change

What this looks like in practice is as follows:

var user = new User();

var createUserCommand = new UserCreation.CreateUser

{

Name = "John Doe",

};

// Validate the command against the aggregate

var userCreatedEvent = user.Validate(createUserCommand);

// Actually mutate the state

user.Apply(userCreatedEvent);

Testability

The example above is incredibly simple to test on. We can literally copy the above usage example into a test case, and verify whether the intended effect is present:

Func<ICommand<User>> createCommand = () => new UserCreation.CreateUser

{

Name = "John Doe"

};

[Fact]

public void UserCreationTest()

{

var user = new User();

var userCreatedEvent = user.Validate(createCommand());

user.Apply(userCreatedEvent);

Assert.Equal("John Doe", user.Name);

}

Alternatively if we wish to solely test the validation logic, and with that usually the business rules, we may simplify our tests a bit to only cover command validation:

[Fact]

public void NameCannotBeNullOrWhiteSpace()

{

ICommand<User> command = new UserCreation.CreateUser();

Assert.Throws<Exception>(() => command.Validate(new User()));

}

Testing for heuristics

To ensure not only the access patterns are solidified, but the behavioural norms are also respected we can start to write a new category of tests I would describe as being meta-tests. With these tests we’re not so much testing the internal behaviour of the commands and events for correctness, but rather whether or not they adhere to certain heuristics. Tests like these allow one to fall back onto conceptual expectations about the behaviour of the code, making reasoning about the functioning of the system significantly easier.

These tests work best when the organization of the assertions is structured in a way that they can be re-used across multiple test cases. When applied at scale one is able to assert the correct functioning of a rather large swath of code at once, providing unprecedented insights into the functioning and stability of the code base.

There are two heuristics for which I’ll provide a sample.

Can the command change the state?

Short answer; yes it can. Should it though?

To check whether this implicit rule about the behaviour of a command is adhered to we can write a test which checks whether the aggregate itself has been modified after validation has completed. Once implemented in a code base this would likely be one of those tests that whenever they fail would first and foremost signal user-error, rather than an improperly designed test.

[Fact]

public void ValidationMayNotAlterState()

{

var user = new User();

createCommand().Validate(user);

user.Should()

.BeEquivalentTo(new User());

}

Above code example with a little help from the Fluent Assertions library :)

Does the command change the provided data?

Validation logic altering the data it must validate is one of those scenarios for which I believe there is no proper use-case. There will almost always be better ways to properly implement such operations. Worst of all is that it alters the expected behaviour of the command in a way which is opaque to the implementing code. As such it would make sense to test commands on this heuristic.

[Fact]

public void ValidationMayNotAlterCommand()

{

ICommand<User> command = createCommand();

command.Validate(new User());

command.Should()

.BeEquivalentTo(createCommand());

}

Debates

My intention is to demo only a minimal example of what this could look like. The actual implementation will most likely depend on the actual requirements. As such one may change the output from the Validate method to be able to provide an error object if validation fails. Alternatively one might want to alter the way both the commands and events handle the Data object, for example to prevent mapping from happening within the constructor. In a real life scenario one would perhaps want to attach metadata to both the commands and events which is not relevant to the domain object itself, but would be for contextual information when using event sourcing as an auditing trail.