Contents ▾

What makes an event sourced domain?

Based off previous work on the design of event sourced aggregates I would like to generalize these efforts to the extent of the whole domain. (I would recommend reading this previous post to gather the required context for this post.) The goal herein is to be able to event source the whole domain, and thus having the ability to restore it to any point in time.

Though I know not all domain objects necessarily need to be event sourced, at this point I suggest having the uniformity in place is a welcome addition. It prevents one from having to spend valuable thought cycles on determining whether a certain domain object is event sourced or not.

Even though I am convinced that event sourcing in itself does not necessarily needs to be a domain concern, it is incredibly handy to have a domain designed in a way that event sourcing can easily be implemented. If it is designed like that, it doesn’t really matter whether event sourcing is used or not. It allows one to reason in a straightforward manner about domain interaction: a command is issued to request a change, and whenever that change is granted an event is provided which can be applied to the internal state. Though event sourcing isn’t needed to work with the domain, implementation of it is supported by default without too much overhead.

With that asserted one might conclude that we’re not really working with an event sourced domain object anymore, but that we have established a particular interaction pattern instead. Instead of method invocations we’re more reliant on the usage of objects to get stuff done. Though the end result will be similar, the level of genericity we can pull off with this approach is highly beneficial in integrating the domain in other layers of the application.

We must however not think that the interaction pattern as introduced previously works for other domain objects outside of the box. Since each type of domain object serves a fundamentally different goal, each type should have an interaction pattern tailored for its specific usage. More about these below.

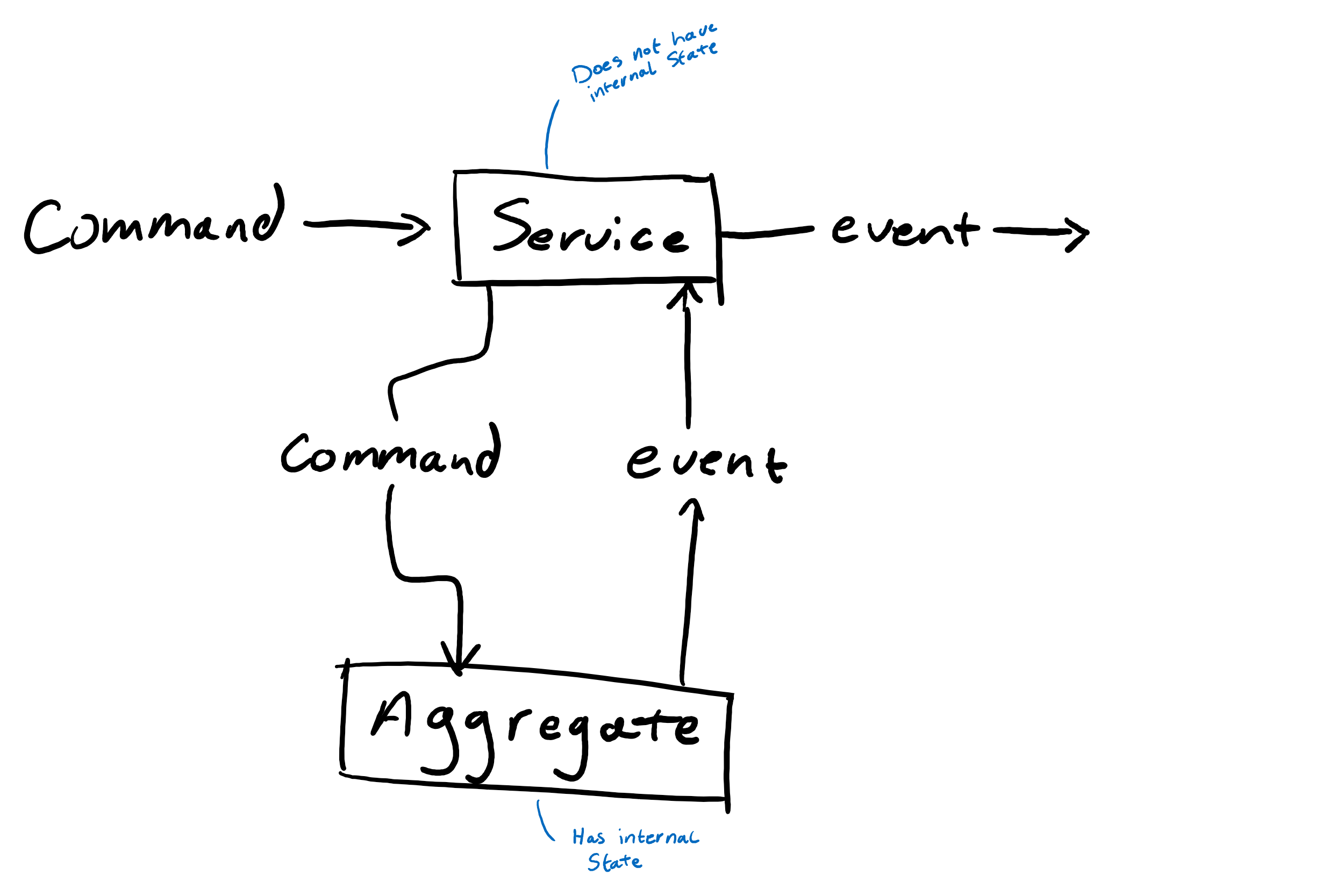

Services

Services work around the fundamental constraint that aggregates may never invoke changes across its own boundaries. Services therefore are responsible for the coordination of changes across multiple aggregates. The interaction pattern with services is similar to the way that aggregates work. They may be invokes through issuing a command, with the only difference that a service may not issue a command, since a service is unable to hold internal state. The events a service returns must be the result of those emitted by the aggregates it encapsulates.

Though in a more traditional domain driven context one might create an service unique to the scope of the problem to be solved (e.g. coordinating change across groups and users at the same time), we previously established that the interaction pattern with the domain must be based on object passing in order for it to be generalized. As such we’re not so much creating services, but rather service commands, which themselves hold all the logic required to run the operation itself.

Maintaining the explicit distinction between “commands” and “service commands” helps understanding the impact a command has across the domain. By calling a service it is directly clear that the change must be coordinated across multiple aggregates.

To support integration and encapsulation in a broader service a command must be invoked upon a specific service. The service itself then can be made responsible for the collection of the required aggregate instances, while the actual logic is embedded in the command itself.

Since services themselves are inherently stateless (perhaps aside from holding references to aggregate instances) they also may not persist events. Service commands are deferred to multiple aggregate commands, which reflect the original commands through the events they emit, and persist on their own internal state. These service commands may therefore only contain logic to check the validity of them.

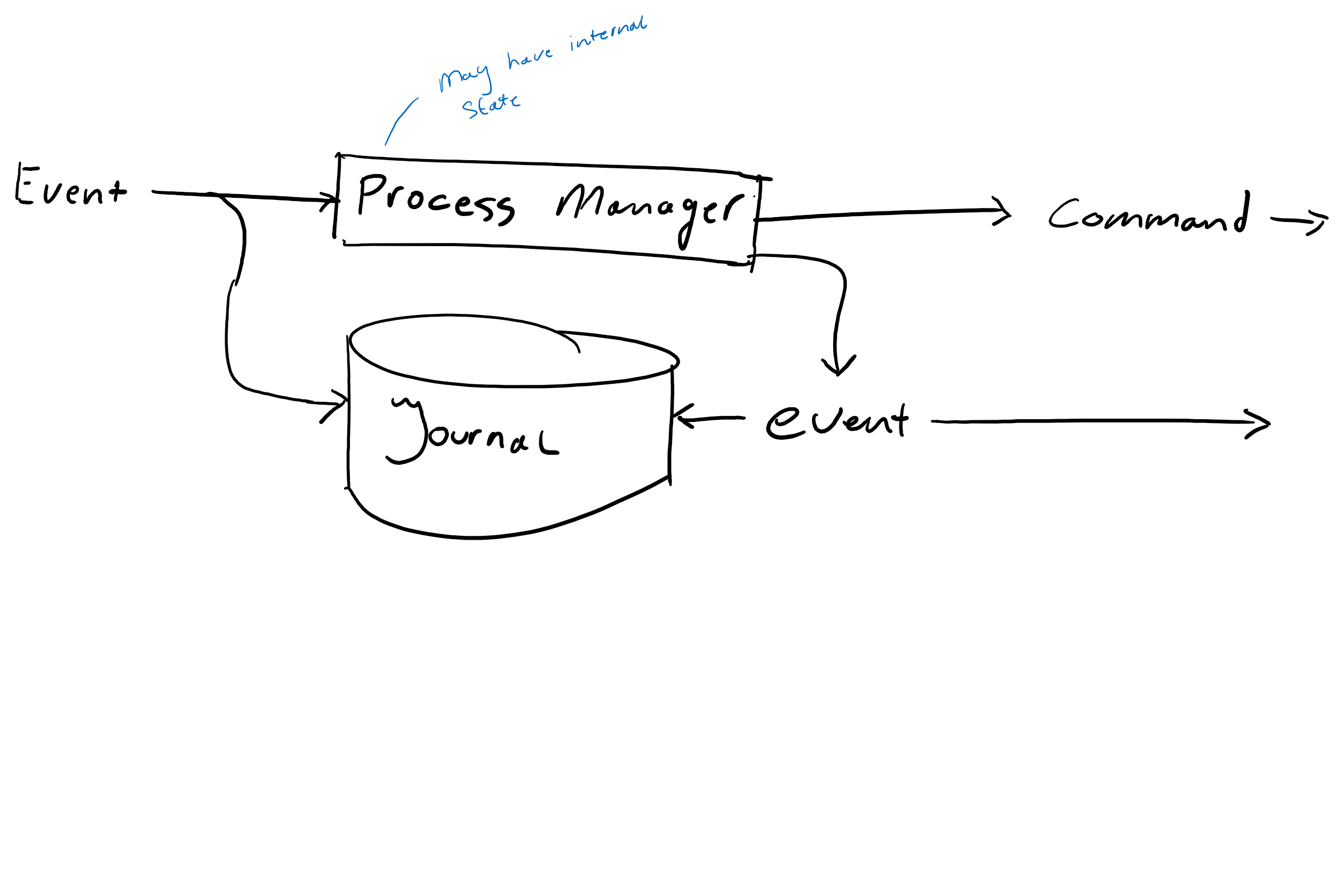

Process managers

Process managers are rather unique in their own way that they cannot handle commands, but may receive domain events, and issue their own events in response. Since the process manager must hold some internal state to influence its further course of action, they must persist the events upon which they react to be able to restore their internal state, and indirectly to ease migratory actions.

In addition to persisting the events it subscribes to, it must also store the events it has emitted itself in order to maintain a complete overview about what it had previously done.

Process managers themselves can be organized in multiple ways;

- Logic to mutate the internal state may be held internally in the process manager itself.

- Logic to mutate the state of the process manager may be applied to the event itself in the same manner that the logic required to mutate the state of the aggregate is attached to it.

Each approach has its own benefits. When adding this logic to the event itself it becomes immediately clear where the event is used throughout the application, whereas the downside is that it makes the event responsible for the mutation of data in different parts of the domain.

Special care should be taken that the event only mutates the process manager’s internal state, and does not trigger any side effects. Something which can be handled in the process manager itself through any suitable approach, such as for example timers, or an evaluation which is executed any time an event is applied. These commands then have the choice between emitting events or issuing commands to other parts of the domain.

Ultimately the fundamental difference to aggregates are the way they handle commands; they do not. Process managers can only respond to domain events, which sums up all they can do.

In relation to a service however the main difference it that a process manager handles (temporally) long running processes, in contrary to services which are able to coordinate operations which can be executed atomically.

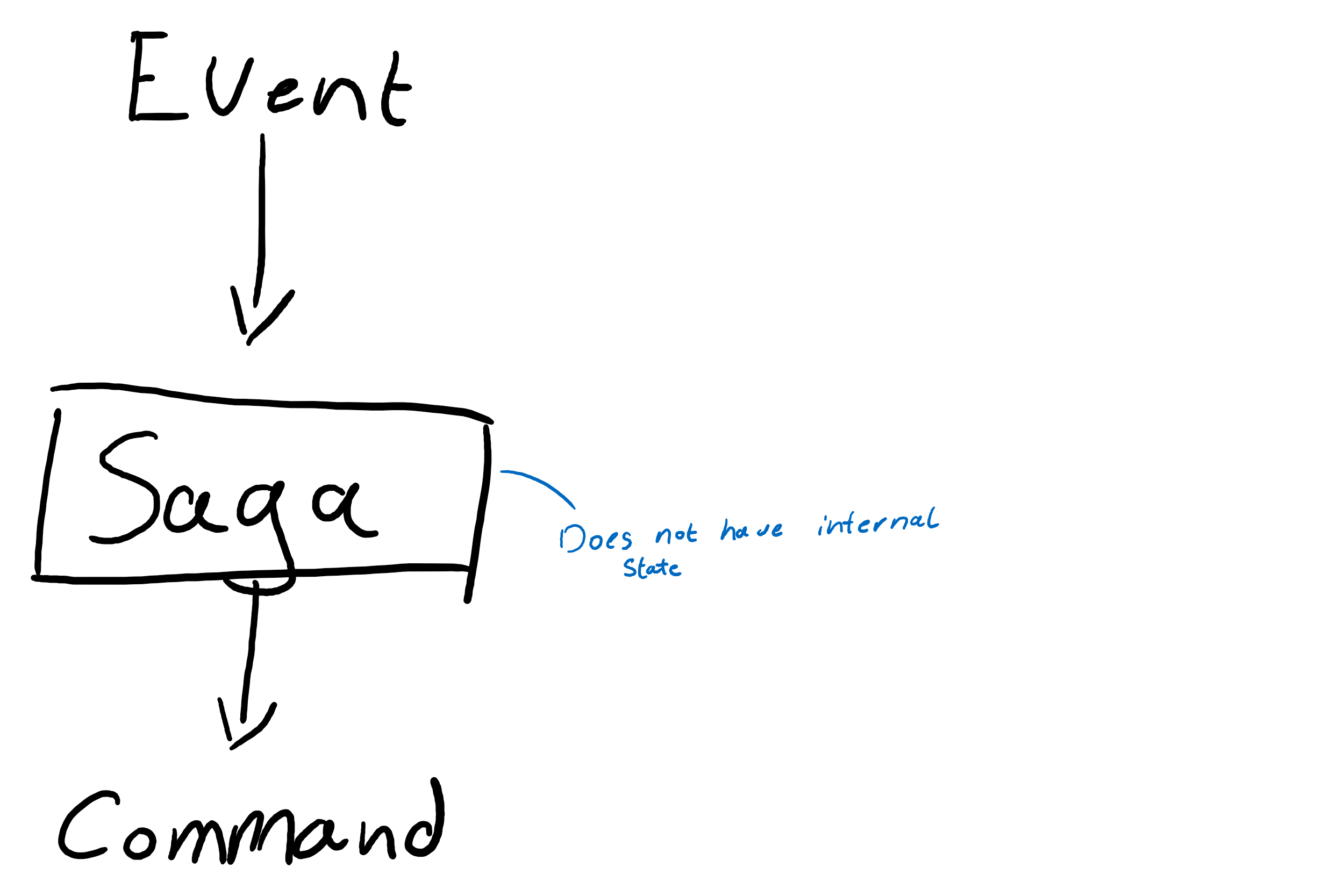

Sagas

A saga is different from a process manager in a way that it can execute compensatory actions in case something goes wrong. Contrary to process managers sagas do not hold an internal state, but have the ability to respond to domain events with compensatory interactions. A saga therefore has the ability to map domain events to new commands, but is decoupled from the business process in a way that it may not proactively evolve a process.

Since the goal of a saga is to hold compensatory actions for failed business processes, the functioning of a saga itself is dependent on the information exposed through domain events. While one may choose to return an exception from a function validating the command, no further action will be invoked in the command that way. In order to make the best use of sagas a failure will need to be recorded through an event, and be emitted as a domain event.

Sagas can then map certain domain events to certain compensatory commands to return the system to a valid state.

Sagas therefore distinguish themselves as being event to command mappers.

Repositories

Repositories are perhaps the exception to the rule that the interaction pattern to the domain is to be expressed through objects. There are multiple reasons for this, whereas the most important one is decoupling. It is almost required that domain objects are only loosely coupled, in order for the infrastructure layer to be able to dictate the actual implementation details. The repository herein is a crucial aspect which facilitates this decoupling within the domain. Since the repository within the domain is solely expressed as an interface, its concrete implementation is supplied through an dependency injection technique later on. Most domain objects with the exception of the aggregate can shamelessly talk against the repository interface with the knowledge an aggregate instance will be returned during runtime.