Delivering complete code

This is a blog post I had been planning on writing for years. Within it I’ll outline a path to be able to deliver “complete code”, and thus a structured process to software development. This post primarily applies to the implementation of line of business (LOB) apps. The process as outlined makes several assumptions about the overarching structure of the application. While it is fairly easy to stay within this structure when starting from a green field, it may or may not be a herculean task to refactor an existing system in a way that fits with this process. If anything, consider your own context before applying any of the processes described in this post, and reflect on the problems you intend to solve for yourself.

The high-level architecture context in which I am operating is as follows:

- There is a single database for persistence

- There is a domain layer which interacts with this database

- There is an API communicating with the domain

From the API onwards any sort of consumer may interact with the features we’re building, but this is none of our business. Whether this is a front-end application, an embedded device or an external service does not matter, nor does the exact type of API used. The API therein is only a means of providing access to the feature we had implemented.

Process

The aspect having the single greatest impact on the effectiveness of the development process is that of risk mitigation, and should therefore be a shaping factor in what this process looks like in practice. Even though not all risks can be fully mitigated, the impact of these risks can be greatly reduced by moving the risks to the front of the software development process.

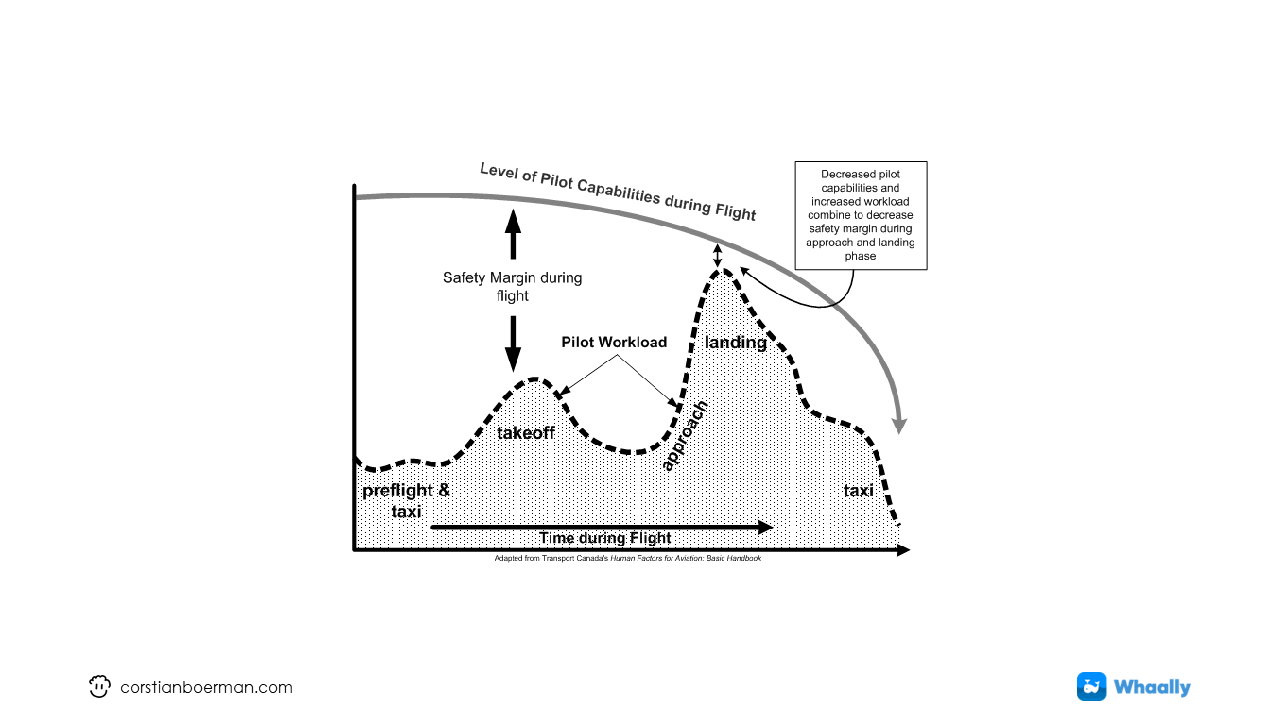

Taking inspiration from the aviation industry, we can see that the risk profile changes during the flight. Takeoff and landing are the two most crucial parts of the flight, with the smallest margin for error. Not only is the risk profile itself changing during flight, but our own capabilities (which are technically part of this risk profile) as well. The margin for error becomes increasingly smaller as we progress, while the impact of failure increases.

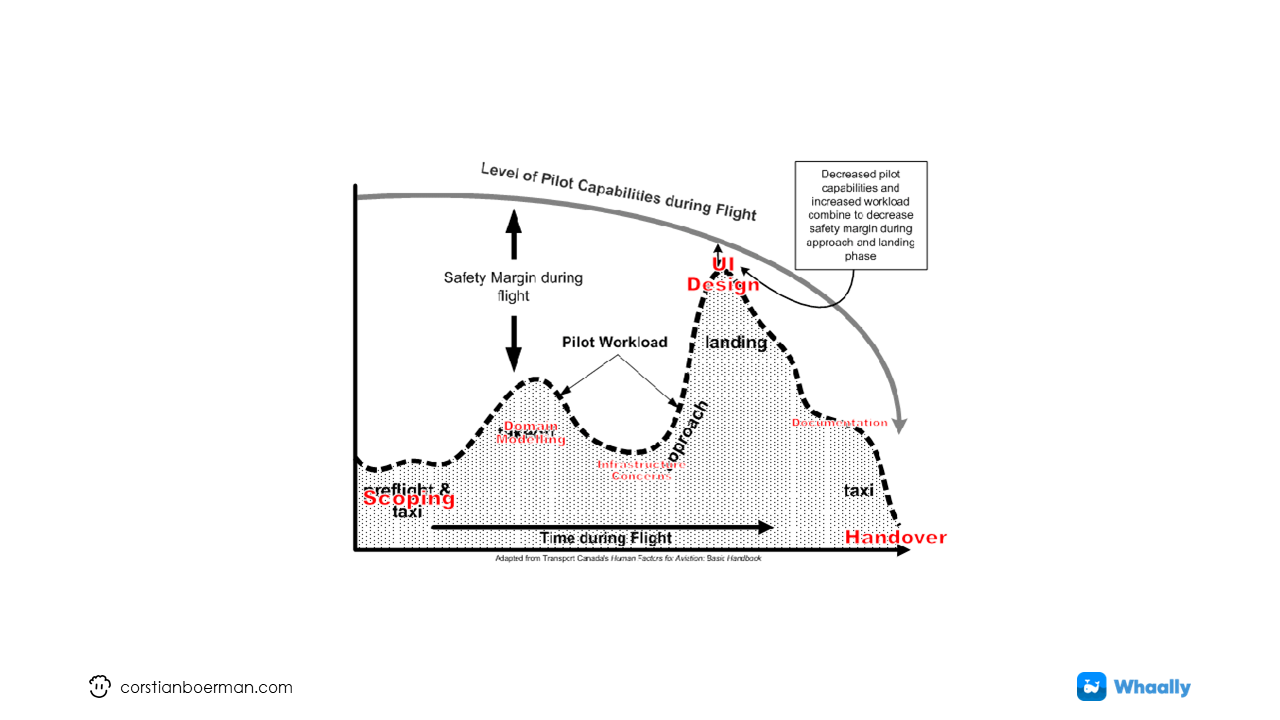

If we were to adapt this chart to software development practices it would look like this;

This process looks as follows:

- Start with scoping;

- What are our intended outcomes?

- What problem are we solving to achieve that?

- Are we solving the right problem?

- How are we going to solve this problem?

- We’ll continue modelling the domain;

- Gain a shared understanding of the business process.

- Any incompatibilities found with the pre-exisiting domain will be found at this point.

- Any blockers discovered throughout this process allow one to go back to the scoping phase. The impact is minimal.

- Infrastructure implementation

- Should be a formality (more on that later)

- (User) Interface development

- Another high-risk operation, for we might discover the process we came up with is not usable in practice.

- Process formalities;

- Releasing said feature (releases should not be tied to deployments!)

- Handover to operations

There is a reason the process is ordered like this, and not that we are, for example, delivering the intended interface first, only after which we are checking compatibility with the domain. It is through the domain layer that we can take very small iterative steps to validate our conceptual models, and there is no other way to achieve this fast paced feedback loop this early in the process.

The tech focused process as outlined here is one which works excellent for small iterative steps. For a higher level process, this approach could very well fit in with an approach focused on delivering business value such as Shape Up.

But now that we have a general outline of the process; how do we actually deliver “complete code”, and what is even our definition of “complete code”?

Complete code

There are so many aspects which need to be considered to be able to deliver high-quality software that it is rather difficult to cover all of them in a single process, especially so for developers just entering the field. Despite that I will try to deliver a system with the following characteristics:

- Maintainability: Code can easily be understood when read, and can easily be changed without fear of breaking other components of the application. The scope of impact is well known or can easily be reasoned about.

- Testability: The code is easy to test, and has good test coverage to be able to identify breaking changes.

- Observability: The system provides the triad of metrics, traces and logs to be able to observe runtime behaviour.

- Stability: The system is designed to be dependable.

- Scalability / Performance: The system can deal with a wide range of load profiles and maintain an acceptable response rate.

- Security: Unauthorized actors may not access the system.

- Integrity: Information contained by the system should remain in a valid state regardless of system failures.

When starting a system from scratch these are a daunting number of concerns to keep track of. Many of these concerns however can be tackled in a structural manner. Observability, stability, scalability and integrity can all be embedded as a responsibility of (generalized) infrastructure, and thus be decoupled from logical concerns. These are then things we do no longer have to think about when implementing logical concerns. Maintainability and testability are two things which must be considered throughout the software development process, and are an ever present challenge. Last but not least security concerns are highly dependent on the context, and may be a cross cutting concern between infrastructure and business logic.

Architectural overview

To cover all of these aforementioned quality aspects I am using my Whaally.Domain library as a base for my own domain model. This library abstracts the domain layer in such a way that it can be fully decoupled from infrastructure. This allows one to implement infrastructure only once and re-use it for all business logic that is implemented.

In practice we will end up with the following projects:

- A domain model

- Domain infrastructure

- An API

In practice I am used to run the domain on top of an actor system for scalability. This makes the domain elastically scalable. Assuming the API properly scales as well this only leaves the database as a hard bottleneck, but given there are scaling strategies for these as well this can all be overcome.

An important assumption for the remainder of this post is that you’re making use of event-sourcing strategies for data storage. Using event-sourcing allows you to decouple your information from the way you’re representing your information. This provides additional flexibility changing your data model without having to go through a difficult refactoring and conversion process to transform your existing data model into a new format. Because the source information in the database are events, we do not have to be all that worried about database migrations either, which simplifies the software development process as well.

Implementation process

Albeit the technical implementation process is highly dependent on the scoping process for determining what to build in the first place, we’re briefly skipping over that and leave it as an exercise to the reader. For initial development the scope of change may be greater than for further iterations on features, which also marginally impacts the speed at which the technical implementation process can be completed.

When following through with this approach the biggest time impact from a bigger scope does not come from the implementation process, but instead from the scoping process. Being clear on what to build should make the development process itself relatively straightforward and predictable.

Nevertheless despite of the scope of the development work, the implementation process remains more or less the same, all covered further onwards.

Domain

When the work is properly scoped out the domain is the first thing to touch. This is the area of the codebase which concisely expressed the existing conceptual understanding of the business domain. Here it can be tested whether or not the new feature properly fits in with the existing conceptual models.

Not only can one use their gut feeling to see whether the new concepts make any sense, but one can rely on new and existing tests as well to assert that the business process works as intended.

The Whaally.Domain library enforces an interaction pattern between various domain components. The benefit of this is that the technical relationship between these components immediately becomes clear, and we can conceptualize the component in its broader context.

It is for an event that we know it is only instantiated through a command, while it effects a state change on the aggregate instance. A consistent structure like this helps reasoning about the impact of code-changes on the remainder of the software. For more a more in-depth detail of the interaction between components, check out the documentation for this library.

Integration with external services

The integration with external services is perhaps the most complicated aspect of the development process. Here not only the state of the local system plays along, but also the state of the external system. A complicated factor herein is the way the integration happens. Is it the current system pushing information to the external system? Should the external system push information into our system? Is there some synchronisation happening? These are all factors to take into consideration to figure out how to design the domain model itself.

Preparing for failure

There are various different failure modes of our software system. Some are technical while others are conceptual. As a general rule of thumb it is important to handle technical failure modes on an infrastructural level, while embedding conceptual failure modes within the domain model, and as such make it part of the business process. This last category of errors concern validation failures, preconditions which are not met, or dependencies which are unavailable (think about payment gateways).

There are essentially two ways we can deal with failure modes:

- We can reject the operation

- We can explicitly model the failure as part of our business process

The benefit of this approach is that it elevates the failure mode as a first class citizen within the domain model. This makes it more explicit for everyone involved in the development process as to what is going on. At the same time it gives visibility to the limitations of the business process, as that is where the errors occur. Needless to say these should be visible in the monitoring tools you’re using to observe runtime behaviour.

Projections

While the domain generally governs the write side in the “Command & Query Responsibility Segregation” (CQRS) pattern, there should be a read side as well from which we can retrieve information. When using an event sourcing techniques we should take care to process these events into projections as well. The information to get out of a system should have been defined during the scoping phase as well, and so even the implementation of the projection should be more of a formality as well.

Since the projections play such a vital role alongside the domain, and are sometimes even depended upon by the domain itself, I myself started placing the projection logic inside the domain as well. The domain (write side) together with the projections (read side) make up the most valuable aspect of a software platform. It’s where the competitive advantage of software is located.

Security

Security is a difficult cross-cutting concern. There are some aspects which should be implemented in the infrastructure, such as token validation, while other concerns should be handled through business logic. There is no one size fits all, however, it can be recommended to limit the size of your core security boundary as much as possible. Of course we should never rely on just a single security measure, however, it is good practice to tightly integrate your security policies into your domain layer.

Once you are in a position that you are to mock your security policies in order to even be able to test your domain, you can be sure that you have a fairly comprehensive system that is difficult to work around. Both for developers building new functionality, as well as adversaries.

For an excellent overview of your options for securing your DDD model, check out this thesis by Michiel Uithol: “Security in Domain-Driven Design”.

Testing

One aspect of the implementation of domain logic which is at least as important as modelling the domain itself is testing the newly implemented behaviour. These tests can be rather concise, and should be focussed on validating whether the edge cases of the business behaviour work as intended. Whether one follows the teachings of Test Driven Development (TDD), Behaviour Driven Development (BDD) or any other development methodology doesn’t really matter herein. As long as the critical aspects are properly tested.

API

After the domain had been implemented, all that remains is to expose this functionality through an API endpoint.

In the more traditional sense of the terminology used within the DDD world this would count as the application layer. In practice it seems to have turned out that it is really difficult to limit business logic to the domain itself as soon as you start to add “application services”. While initially these services only compose behaviour provided by the domain, over time more and more business behaviour starts leaking out of the domain.

It is for this reason that I find it more beneficial to think about the application layer as being a proxy to a domain. Something passing operations onwards to the domain without further modification. Just an implementation artefact to guide the operation across the multiple protocols it encounters along the way until it eventually reaches the code itself.

For our purpose it does not matter what this API endpoint looks like. Whether it is a more traditional REST API, a GraphQL endpoint or perhaps even a custom binary protocol over TCP; it doesn’t matter. All that does in fact matter is that the API should take care to forward the operation with the least amount of effort.

As a practical challenge I have made it a point to route the operation into the domain, and the response out of it all through a single line of code. This ensures that the business concepts as had been defined within the domain are preserved as well as possible. This truly makes the API just another interface to the domain layer, and allows people to reuse the same business concepts, whether they are working on the backend, or are implementing something on the other side of the API.

To make this process even more smooth it is completely acceptable to re-use commands and events as models used by the API. Changing these operations against the domain then means an automatic change against the API as well, which in my humble opinion is a feature. As long as there is no hard dependency on the model of the aggregate we should be fine, flexibility wise.

Integration Testing

As a last step to validate the correctness of the application I’m building automated integration tests against one or more APIs. By doing so I have assurance that all the nitty gritty details work as intended. As such an integration test covers:

- The correct functioning of the API

- The correct implementation of security functions

- The correct (de)serialization of models along the way

- The correct functioning of the actor system

- The correct functioning of the domain layer

- The correct functioning of the database

Where unit tests are responsible for the correct functioning of the domain, the integration tests are responsible to ensure that all components have been put together in a correct composition. As such we do not have to deeply test the business logic either.

After we get the integration tests to pass we can be fairly sure that the feature we had just developed functions in production as well.

While functional manual testing of the application still happens to a certain extent, the use of automated integration tests allows a much shorter feedback cycle than would otherwise be possible. Rather than minutes we’re now speaking about seconds.

Personally I always feared integration tests, for the difficulty of dealing with dependencies outside of the solution, such as data stores etc. If this is you; these two resources help you get started:

Releasing

The final step in the process is to release the new feature into production. It should be noted that releases should be decoupled from deployments! The trick to do so is to use feature flags to toggle certain features on or off. This reduces the risk of a feature breaking production, while still continuously deploying to production. In that sense feature flags are an essential part of continuous integration and deployment. Throughout this process the product could have been deployed to production multiple times already, even though it had not yet been finished. The benefit of doing so is that it instils confidence in the correct functioning of the product, and any potential errors are caught early on in the development process.

Closing remarks

The technology as is combined with the process makes it such that the software development process itself becomes a rather dull and predictable exercition. By repeating this process in short cycles it has the potential to become a habitual practice, simplifying the process even further, as if it were a reflex. This in turn allows us to spend more time looking around us. Reflecting on the goal we want to achieve, and figuring out which problems we need to solve in order to do so. It allows us to focus more on the world, rather than the software we are writing. After all we should be writing software to achieve a certain goal, rather than to write software for the mere goal of writing software.